Personal

Growing up

I was born in 1955 in Portsmouth, a scruffy, lively, dockyard city on Britain’s south coast. Both my parents had to leave school before the age of fourteen and I inherited from them a deep respect for books and learning, together with a sure knowledge that educated people and intelligent people were not one and the same.

The local public library was my mother’s equivalent of church. I was the first person in the wider family to go to university, thanks to three years of a free government education grant. What would happen to a girl like me now in an age where libraries in the UK are being closed down and higher education costs a fortune?

Academic life

I’ve been in and out of academic life. I was nearly thirty when I got my first fulltime lectureship in the Humanities at Brighton Polytechnic, where we set up a degree in the unchartered territory of ‘British Studies’. From 1995 I’ve taught part-time, with the odd break for writing; I’ve generally left jobs in order to finish a book. Most recently, until 2011, I taught one semester a year as a Professor in Modern English Literature and Culture at Newcastle University. Although I owe much to my former colleagues and students, I now call myself an independent scholar.

Literary journalism

I’ve been writing literary journalism, off and on, for nearly forty years - publishing my first reviews and fiction in the feminist magazine, Spare Rib (I was a later on the editorial collective of Feminist Review).

In the ‘80s I wrote for the New Statesman, the Guardian, Sight and Sound; most recently I’ve been a contributor to the London Review of Books.

I’ve always believed that it was possible to span the great divide in British culture between an intelligentsia or educated elite who speak only to each other, and a broader readership; and to do so without having to ‘dumb down’ or, alternately, indulge in jargon. (It’s fine to have to look up the occasional abstruse word in a dictionary!)

Working with historians

After my first husband, the historian Raphael Samuel, died in 1996, I helped establish an archive of his papers and a History Centre which would evoke the spirit of his work - intensely engaged with every kind of history and with historians both from within and outside the university system.

After my first husband, the historian Raphael Samuel, died in 1996, I helped establish an archive of his papers and a History Centre which would evoke the spirit of his work - intensely engaged with every kind of history and with historians both from within and outside the university system.

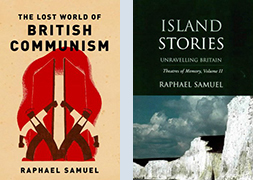

I put together two volumes of Raphael’s essays - Island Stories: Unravelling Britain (1997) and The Lost World of British Communism (2006) - and I remain on the Centre’s Management Board.![]() Visit www.raphael-samuel.org.uk for its range of public events and seminars

Visit www.raphael-samuel.org.uk for its range of public events and seminars

A mongrel

Now that I am writing full-time I think of myself as a mongrel, neither historian nor literary critic, neither biographer nor cultural commentator - there’s something of them all in my make-up.

My books have been mixed in genre but common themes run through them: not least, the capacity human beings have to generate their ‘poor dreams and fabrications’ in the face of an often indifferent or harsh society. And what is writing if not wishful thinking?

Alison (centre) c.1962, with her cousins in her grandmother's backyard. We are in our ‘Sunday best’ - the matching white socks and sandals, my elaborate bows. As children we were rarely photographed; the arm-wrenching embrace suggests an adult posed us. I wasn’t close to Kelvin (who is leaning away) or to Marilyn, who was visiting from the country. Her father took the photo - is it his nostalgia that suffuses it?

Alison (centre) c.1962, with her cousins in her grandmother's backyard. We are in our ‘Sunday best’ - the matching white socks and sandals, my elaborate bows. As children we were rarely photographed; the arm-wrenching embrace suggests an adult posed us. I wasn’t close to Kelvin (who is leaning away) or to Marilyn, who was visiting from the country. Her father took the photo - is it his nostalgia that suffuses it?

![]()

Great Expectations is a comedy of forgiveness towards one's younger self. Dickens's famously unruly humour is part of his firm belief in wishful thinking, in our capacity for poor dreams and fabrications, and the obstinate hope that there might be places where the long arm of rank and distinction cannot reach. What larks, as Joe says, what larks.

From: Rereading Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations: www.theguardian.com/books![]()

© Alison Light 2024